Eight Billion People

Today is the last day when the number of people alive will start with a seven. Sometime late Tuesday afternoon, or perhaps early Wednesday morning, the population will cross the eight billion mark. When I was a kid, the number they taught us in school was five billion. By the time I was in college, it was up to six, and a decade ago it hit seven.

Now it’s at eight. Is this just a factoid, a little piece of trivia only good for winning pub quizzes?

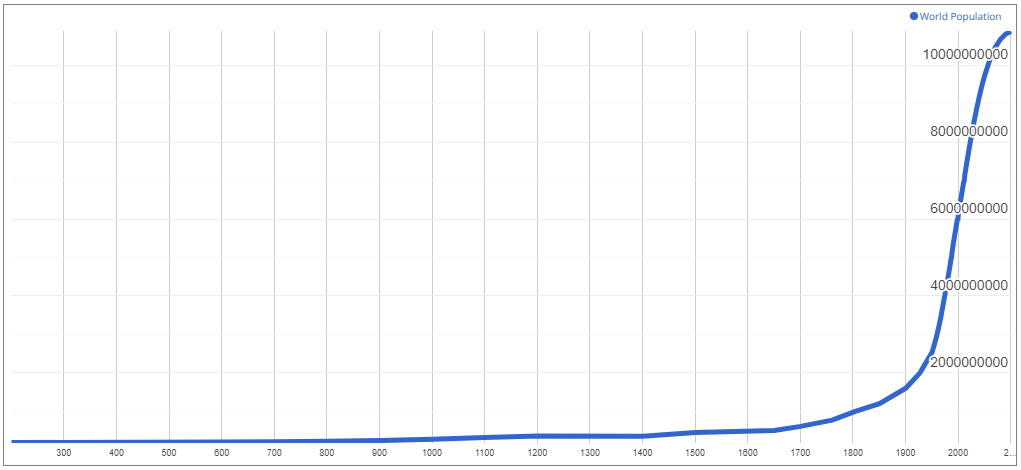

I don’t think so. Oh, the specific number is arbitrary enough. But the trend, the larger pattern — that’s important. Take a look at this graph:

For most of human history, humans were counted in the millions, not billions. We hit one billion around 1800 and have been growing exponentially ever since. I haven’t been around quite long enough to see it double in my lifetime, but my parents have. Here’s the interesting thing: it’s not likely to double again, not unless something drastically changes. The growth rate is slowing, the population curve is flattening out, and current projections have the population stable at around 11 Billion by the year 2050. Which means the past century may be completely unique - the only time in all of history when six billion new humans were added in a single century.

Ecology Analogy

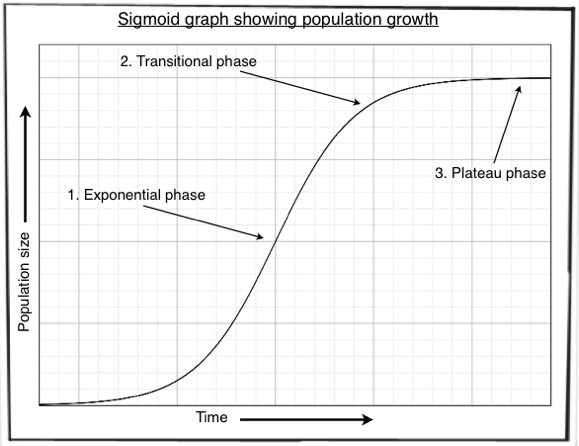

In ecology, they sometimes draw this sigmoid growth curve and divide it into phases:

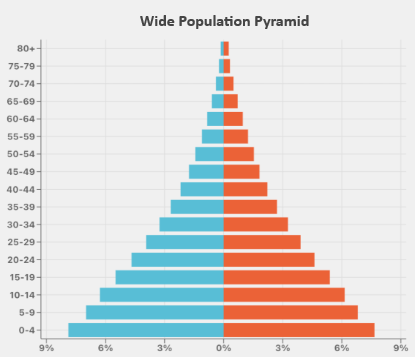

In a typical ecological model the maximum population, called the carrying capacity, is determined by food supply or predation, while in the case of humans it seems to be driven by the demographic transition. But the effect is the same: there is a period of growth where there are always more young people around than middle aged people, and more middle aged people than elderly. Resources seemed unlimited and growth was unchecked. The population pyramid is very wide at the bottom:

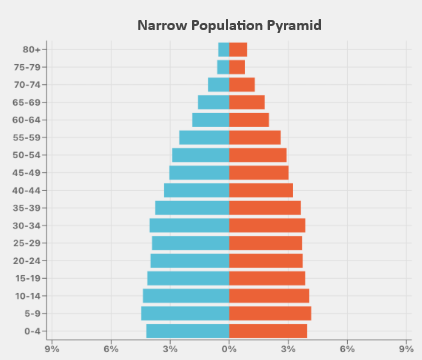

However, as we begin to approach the carrying capacity, everything changes. We hit a plateau: growth slows and eventually disappears entirely. Competition over scarce resources increases. The population pyramid narrows and there relatively fewer young people around:

Japan provides a sneak peek into what we’re likely to expect domestically over the next few decades, and globally over the next century. In Japan, the growth rate has already become negative, resulting in a large elderly population that is straining their social support systems, a weak economy, and little opportunity for advancement.

Regime Shift

Here’s a little piece of folk wisdom from my days as a physics student: “If any quantity changes by more than an order of magnitude, double check all your approximations. They may no longer be valid.”

For example, you’ve probably heard of turbulent and laminar flows:

Both are fluid flows ultimately based on the same equations. There’s no hard cut-off between the two. The only difference is which approximations we use. But they behave completely differently; so much so that it’s easier to try to understand them as two separate phenomena.

Changes in scale often result in this kind of so-called regime shift.

“Building a four-foot tower requires a steady hand, a level surface, and 10 undamaged beer cans. Building a 400 foot tower doesn’t merely require 100 times as many beer cans.” - Steve McConnell

We can tell a similar story across a wide variety of problem domains. A human can run about 8 miles per hour. To go from 8 mph to 80 mph, you don’t just need to “run harder.” You need to build an engine or jump off a cliff. To go from 80 to 800, you need a jet and an airframe specifically designed to break the sound barrier. At 8,000 mph the physics of airflow go through another qualitative shift as we enter the hypersonic regime. Now you need a scramjet and a way to dump all the excess heat. Each order of magnitude isn’t just harder, it’s completely and qualitatively different.

Rate of Innovation

Population is not the only thing that’s been growing exponentially. In his 1975 book Science Since Babylon, Derek de Solla observed that the number of PhDs being issued was doubling roughly every 20 years. This fact is often communicated with the vivid expression, “90% of all scientists who have ever lived are alive today.”

While some of this is driven by population growth, increased availability of education also plays a role. As a result, this number is actually growing faster than population. And that might continue even after population growth has levelled off.

All those scientists and engineers building and figuring stuff out cause a lot of change. And the rate of change increases proportional to the number of scientists, which is only going up. Even as population growth levels off, technological innovation is only going to speed up.

“In the whispering quiet of Heaven’s night you imagine you can hear the paradigms shatter, shards of theory tinkling into brilliant dust as the lifework of some corporate think tank is reduced to the tersest historical footnote…”

- William Gibson, Hinterlands

The first time I really felt this firsthand was working with JavaScript frameworks circa 2010. It was a wild time. Entire frameworks would come into existence, become de facto standards overnight, and be considered outdated and untouchable a year or two later.

Oh, you’re still generating HTML on the server? Haven’t you heard about AJAX and XHR? The X stands for XML which is going to be the Next Big Thing. Of course, we would never actually pass XML; that’s so last year. (Yeah, that includes XHTML; we’re moving forward with HTML5 instead because it turns out getting developers to consistently close their tags is really hard.) No, everyone is passing JSON to REST APIs now. Actually, use jQuery to do it for you. What, you’re still using jQuery? You gotta get up to speed with MVC frames like AngularJS. They’ll bind your data to HTML for you. Thank you for being an earlier adopter of AngularJS 1.0; please transition your project to AngularJS 2.0 where we’ve broken backwards compatibility every way we can think of, plus a couple new ways we invented just for this project! Actually, let’s all just use React. (How about Vue? Oh, I’m fine; how are you?) Of course, you’d never actually write your own HTML/CSS; you’d use components and a CSS framework like Bootstrap. But obviously component libraries are rigid and inflexible and we should be writing our own “lightweight” HTML. Don’t forget to add responsive design! And support Retina displays! And touch events. Firefox is great but don’t forget to bend over backwards to support IE6 - just kidding, it’s all Chrome now. Don’t use Python on the server — use Node.js. Oh God NPM is so bad but never mind: gotta move fast, break things. Don’t use JavaScript — use CoffeeScript or TypeScript. Actually, JavasScript is fine now. (Thanks ECMA!) Here’s one way to package JavaScript into modules. Here’s another, incompatible way. Maybe a third-party library can help unify the two? Oh, now there are three incompatible ways to package modules.

My suspicion is that kind of maelstrom will become increasingly common as the overall rate of innovation continues to increase. Workers in a variety of fields will have to find their own strategies for coping with a constant, overwhelming flood of change. Programmers were able to adapt by moving to agile methodologies and CI/CD pipelines but then again, programmers have always been uniquely good at writing their own tools. Other fields and industries won’t necessarily have that capability.

Before and After

If the projections are true and the population does stabilize at around 11 billion, then I think future historians will draw a sigmoid population curve and divide history into three phases - the low population era of ancient and medieval history, the transitional growth era we’re in now, and the steady state era of what they will think of as “modernity.”

What will that new world look like? Well, there are some things we can say:

| Category | Transitional Era | Future Steady State |

|---|---|---|

| Population Growth | Exponential | Flat |

| Population Pyramid | Wide Base of Young People | Narrow Pillar |

| Population Distribution | Sparse | Dense |

| Innovation Time Scale | Decades | Years |

| Natural Resources | Plentiful | Constrained |

These are the first-order, easily predictable effects. But they already paint a picture of a very different world which will lead to second-order effects which are much harder to predict.

To take one trivial example, currently workers in many fields are expected to move up to management after they have a decade or two of experience. But that model only works if there’s a cheap and plentiful supply of young, inexperienced people to swell the ranks. If the population pyramid drastically narrows, that basic assumption will fail and executing projects where all the real work is done by the least experienced people may no longer be the dominant strategy. Of course, cultural lag means it could take a long time for people to realize that the way they’ve always it their whole life no longer works. Concepts like “expected career progression” are baked into our culture at an almost subconscious level.

There’s never going to be a specific date we can point to and say, “there! that was the day the modern world began!” But eight billion people on November 15th, 2022 is as good a date as any to nominate for that honor. It’s time we start thinking seriously about the end of exponential population growth, the increasingly constrained resources of our planet, and the dizzying rate of change that will characterize the rest of our lives.