Grifters, Skeptics, and Marks

We are in a golden age of grift. Where adventurers once flocked to California or the Yukon because “there was gold in them thar hills,” the fastest way to get rich today is by fleecing suckers. We’ve got crypto rug pulls, meme stocks, nutritional supplements, MLMs—anything to make a quick buck. Financial professionals frequently joke, “crime is legal now.”

This is hardly new. The Great Depression brought with it a wave of con artists, as portrayed in movies such as Paper Moon or The Sting. A century earlier, Mark Twain wrote of the innumerable swindlers and card sharps operating along the Mississippi River; indeed, Twain himself lost most of his own fortune investing in fraudulent investment schemes. When conditions are right, they seem to crawl out of the woodwork.

Not that things were better in the past. The medievalist Umberto Eco seems fascinated with pre-modern conceptions of truth and has written several novels exploring frauds, liars, and magical thinkers. Baudolino in particular is about how easy it is to take advantage of people in a superstitious age, and how easy it is to get lost in a maze of half-truths if you try to do so.

Is this just the new normal? Is it just going to keep getting worse? Or is this just the high watermark in a cycle as old as civilization? If it is cyclic, is it driven by external circumstances such as war or poverty, or does the oscillation arise naturally from the dynamics of the system?

Such ivory tower questions have a pragmatic application: should we expect grift and corruption to get worse, stay the same, or get better over the next decade?

The answer, I’d argue, lies in a moderately obscure mathematical theory from the 1980s.

Evolutionary Game Theory

The version of game theory most people have seen is the rational-agent sort: perfectly informed players maximize utility, best responses snap into place, and equilibria have the clean finality of a solved puzzle. Evolutionary Game Theory (EGT) is different. It assumes that all strategies exist in the population and that success in games leads to reproductive success which slowly increases the relative proportion of that strategy in the population over time. Strategies that earn higher payoffs become more common. Strategies that earn lower payoffs decline.

This is the framework John Maynard Smith popularized in Evolution and the Theory of Games. The book is now mostly read by specialists, but it contains a small number of ideas that are so widely applicable that once you see them, you start seeing them everywhere.

Note that triangle diagram on the cover of the book; we’ll be revisiting that visualization several times.

Source code available in the Jupyter notebook. It even has a cell with interactive widgets so you can play around with the parameters in real time.

GSM Model

We’re going to try and model the prevalence of grifters with a EGT model with three strategies, then use the mathematical tools Maynard developed to study that model. While such a simplistic toy model won’t even try to capture all the nuances of the real-world, we can hope for qualitative insights. The three strategies are:

- Grifter: attempts exploitation when possible.

- Skeptic: pays an ongoing cost to avoid being exploited.

- Mark: trusts by default; cooperates cheaply, but is vulnerable.

We can formalize these strategies within EGT by defining a payoff matrix:

| Players | Grifter | Skeptic | Mark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grifter | -grifter_loss | -grifter_loss | grift_gain |

| Skeptic | -skeptic_cost | mutual_benefit - skeptic_cost | mutual_benefit - skeptic_cost |

| Mark | -mark_loss | mutual_benefit | mutual_benefit |

When a Grifter meets another Grifter or a Skeptic, the scam fails. The Grifter wastes time and effort and incurs a loss. But when a Grifter meets a Mark does the strategy pay off: the Grifter successfully exploits the Mark and gains a sizable reward.

A Skeptic never gets scammed, but pays a constant price for vigilance. When a Skeptic meets anyone—Grifter, Skeptic, or Mark—they incur an constant overhead cost, which represents costs investing in education and doing due diligence. When interacting with honest counterparts (Skeptics or Marks), they still achieve mutual cooperation, but still have to pay the cost for their caution.

A Mark is trusting and unguarded. When a Mark meets another Mark, everything goes smoothly: they cooperate without hesitation and both receive maximal payoffs. Things go almost as well when they meet a Skeptic; after the Skeptic has done their homework the two are able to cooperate without issue, and the Mark still receives a maximal payoff.

It’s only when a Mark encounters a Grifter that things go south. When that happens, the Mark gets exploited and incurs a large loss.

The specific parameters don’t affect the qualitative outcome much, but here are some reasonable parameter values for concreteness:

| parameter_name | value | note | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mutual_benefit | 1.0 | mutual benefit of cooperation | |

| skeptic_cost | 0.2 | overhead of being a skeptic | |

| grift_gain | 1.5 | payoff for a Grifter exploiting a Mark | |

| mark_loss | 2.0 | loss suffered by a Mark when exploited | |

| grifter_loss | 0.5 | cost of a failed grift | |

With those parameters, the concrete payoff matrix is:

| Players | Grifter | Skeptic | Mark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grifter | -0.5 | -0.5 | 1.5 |

| Skeptic | -0.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Mark | -2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Replicator Dynamics

To turn payoffs into population dynamics, we use replicator equations: each strategy grows (or shrinks) in proportion to how well it is doing relative to the population average.

Here is the simple, discrete-time simulator I used:

def replicator(populations, A, delta=0.05, N=2000):

"""

Given an initial vector of `populations`, an payoff matrix `A`, a step size

`delta`, and a number of iterations `N`, return the trajectory as a 2D

numpy matrix and the final population as a 1D numpy array the same shape as

the population.

"""

# ensure populations is a normalized numpy vector

populations = np.asarray(populations, float)

populations = populations / populations.sum()

# initialize the trajectory with the initial conditions

trajectory = [populations.copy()]

for _ in range(N):

# payoff for this iteration

fitness = A @ populations

# update population in direction of the most successful strategy

average = populations @ fitness

populations = populations + delta * (populations * (fitness - average))

# avoid extinction and normalize

populations = np.clip(populations, 1e-6, 1 + delta)

populations = populations / populations.sum()

# track the full history of population trajectories

trajectory.append(populations.copy())

return np.array(trajectory), populations

This is not the only way to do it but works well enough for our purposes. Note that the simulation returns the complete trajectory (history) of each population over time: we are not searching for an optimal strategy; we are watching what happens when strategies compete and the winners become more common.

Results

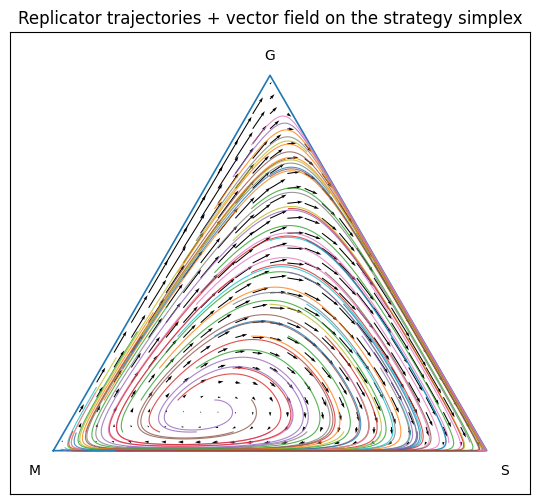

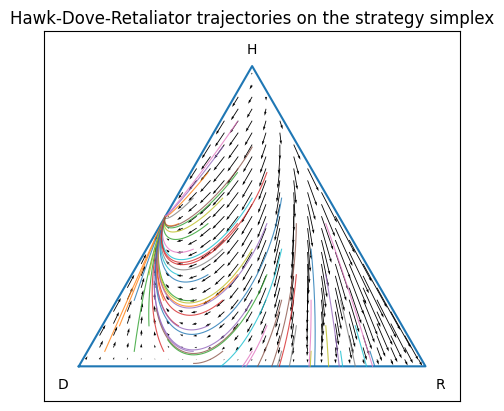

The state of a three-strategy population fits naturally on a simplex: a triangle where each corner is a pure population (100% Grifter, 100% Skeptic, 100% Mark), and each interior point is a mixture. Several different trajectories are shown as colored fields, each with different random initial conditions, and a vector field showing the evolutionary pressure at each point is overlaid.

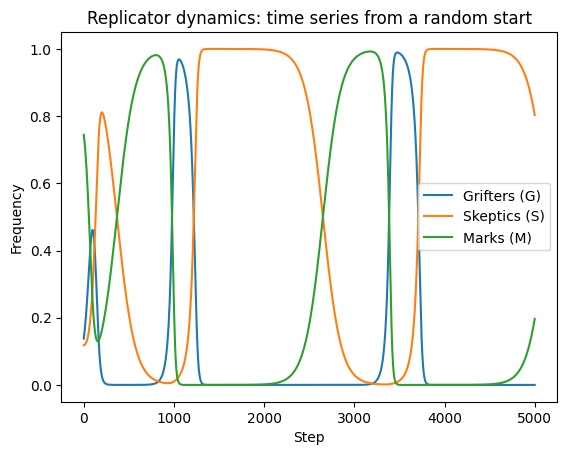

It’s also instructive to look at the longitudinal view, plotting the three populations as a time series:

We can see the system does not settle down to a single equilibrium point but instead falls into quasi-periodic cycles. This is the signature of “non-transitive” games such as rock-paper-scissors; in such games trajectories orbit rather than converge.

Our game is “non-transitive” because success is a function of the current population mix, and that very success always leads to a different mix:

- Marks prosper when grifters are rare, because trust is efficient.

- Grifters prosper when marks are common, because exploitation is easy.

- Skeptics prosper when grifters are common, because vigilance pays for itself.

In models like this, a few different long-run patterns are possible: the system might converge to one stable balance (a fixed-point attractor), it might circle around in a stable loop (a limit cycle), or it might swing closer and closer to each corner in turn, spending long stretches dominated by one strategy before shifting again (a heteroclinic cycle). The qualitative behavior is roughly the same, though: periodic cycles, not a steady state.

Hawks, Doves, and Retaliators

A useful contrast is the classic Hawks/Doves/Retaliators model, which is often used as a first EGT example because it tends to settle to a stable equilibrium point.

Such a stable equilibrium point is called an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS).

Why does HDR converge to an ESS while GSM does not? The Retaliator strategy goes extinct and stays extinct because it bears the full cost of policing Hawks itself. In contrast, the Skeptic in GSM is not concerned with punishing Grifters but simply avoiding them.

Conclusion

If you believe the assumptions of the model, the implications are pretty clear. Grift is cyclical, and any period of high grift will soon give way to a period of high skepticism, which will last until enough time has passed for people to once again forget the lessons they’ve learned. In other words, the current generation of grifters is putting on a masterclass in spotting con artists and it won’t be long before their tricks are well known enough to stop working; consider NFTs, which crashed pretty hard once people saw through them.

OK then,should we believe the model? On one hand, obviously not. It’s a ridiculously simplified caricature of human behavior and every aspect of the model can be legitimately challenged. In some ways we can say it is definitely wrong; for example, it has the various populations crashing to near zero with each period, whereas in the real world the change is more a matter of degree. On the other hand, sometimes very simple toy models do somehow capture the essence of a phenomenon. “All models are wrong, but some are useful,” to quote George Box. If nothing else, I think this model shows that a certain fluctuation in the number of con artists arises naturally from the dynamics of the system, without the need for any external drivers.

I’d like to leave you with this timeless piece of advice:

Exercise caution in your business affairs; for the world is full of trickery. But let this not blind you to what virtue there is; many persons strive for high ideals; and everywhere life is full of heroism.

—Max Ehrmann, Desiderata